Anni Krummel Reinking is a Graduate Assistant and Ed.D. student in the School of Teaching and Learning at Illinois State University. She is a former preschool, kindergarten, second grade, and early childhood special education teacher. In this post, Anni describes how teachers can cultivate responsibility in young children with some great practical tips for doing so!

Anni Krummel Reinking is a Graduate Assistant and Ed.D. student in the School of Teaching and Learning at Illinois State University. She is a former preschool, kindergarten, second grade, and early childhood special education teacher. In this post, Anni describes how teachers can cultivate responsibility in young children with some great practical tips for doing so!

Teachers, especially early childhood teachers, build a foundation for students to learn responsibility through choices and consequences (Head Start, 2014). While building that foundation, with the help of parents, it is important to emphasis strategies, character traits, and skills that can be applied to children developing and living in a diverse, high tech, and democratic society (Popkin, 2014). Children are growing up in a society that has changed over the generations and is continually changing.

Arguably, parenting styles and teaching styles are very similar and have worked reasonably well. However, when we think about the past, our society is much different today. What worked fifty, twenty, or even ten years ago does not work today in the society we are living in. It is our job, as educators, to cultivate responsibility within our students in order to create future citizens who can problem-solve, communicate, and cooperate (Head Start, 2014; Popkin, 2014).

Where do our children learn these skills in order to increase their courage and self-esteem? Children learn it from teachers and parents. How do teachers and parents create situations to cultivate responsibility increasing children’s self-esteem and courage to communicate and problem-solve effectively? The answer is simple, through discipline, which includes choices and consequences, along with consistency.

Dr. Popkin (2014), a psychologist who focuses on raising children today, brings attention to the importance of creating an active environment for everyone, rather than a “Dictator” (Autocratic) environment or a “Doormat” (Permissive) environment. According to Dr. Popkin, in a Dictator society or environment, children are lead by fear and are compliant because of rewards and punishments.

In a Doormat society, children have absolutely no boundaries and rules are not enforced. However, in an Active environment parents and teachers are able to take the strengths from the autocratic and permissive styles to create an environment of communication and problem solving. When teachers and parents are able to create an active, or working together, environment children are able to develop critical character traits and skills. These traits and skills are needed to develop courage and high self-esteem (Popkin, 2014).

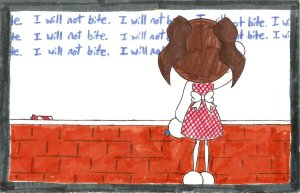

Today, some professionals and researchers argue that schools are being run in a more “dictator” mentality. For example, when teachers tell their students what to do, “because they said so,” children are not able to develop a voice or a sense of ownership in their life or environment. In this type of school building, students who know how to follow the rules and “play the game” survive. However, children who are still learning how to make acceptable choices are continually punished through losing rewards other students are receiving. They are not punished through physical violence in school buildings. However, missing out on the same activities day after day, quarter after quarter, year after year, is a type of punishment or teaching through hurting (Popkin, 2014). But, providing opportunities for choices followed by consequences that are NOT focused on rewards and punishments builds a child’s self-esteem and creates an environment where everyone has a voice and “power” in their own life (Kohn, 1993).

As teachers, or parents, we may walk into a situation where rewards and punishments are used to manage our students or the students in our school buildings. So, what can we do? The top five ways, described by Dr. Popkin (2014), are:

- Encourage

– Make sure to encourage your students

– “Catch them being Good”: Don’t wait for children to misbehave, expect them to follow rules and procedures and acknowledge the small steps

- Communicate, communicate, communicate

– Help your students think through the pros and cons of the situation

– Ask questions so they are able to think through all of the possible outcomes of choices

- Mutual Respect

– Give choices (That you can live with)

– When children are given choices they feel as though they are valued as an individual

- Provide consistent and logical consequences

– Teachers need to assist students in learning boundaries and developing responsibility

– It is important to remember, though, that the consequence must match the misbehavior (i.e. A student throws a toy, when they know the rules of the classroom. The logical consequence would be to lose the privilege of playing with that toy for an amount of time.)

– It is also extremely important to communicate with students during logical consequences so they understand and link between their behavior and the consequence.

- Role-model appropriate ways to problem-solve

– Provide the words or ideas students or children may need to solve a conflict with a peer

– This includes how to handle emotions, such as anger, appropriately for situations

We are responsible for cultivating responsible future citizens and that cultivation begins in early childhood through experiences, conversations, and choices. When children feel as though they have a say in their high tech, diverse, and democratic society, they begin to build confidence, courage, and a high self-esteem. Let children have a voice, sometimes what they say may surprise you!

References

Head Start. (2014). Domain 6: Social and emotional development. Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/ttasystem/teaching/eecd/domains%20of%20child%20development/social%20and%20emotional%20development/edudev_art_00016_061705.html

Kohn, A. (1993). Choices for children: Why and how to let children decide. Phi Delta Kappan 75(1), 8-21.

Popkin, M. H. (2014). Active parenting: A parent’s guide to raising happy and successful children (4th ed.). Canada: Active Parenting Publishers.

Recent Comments